I have to update a game rules document today. It might be my least favorite part of being a game designer. Like, maybe worse than a bad game pitch. The process is a mix of tedium and anxiety, and it might rank second only to the very first playtest as the step that induces the most imposter syndrome for me.

While most hobby games these days are often initially learned by players via having a friend teach or watching a video, somebody’s got to be the first link in that chain. The rules document is the first proof to that person that the game actually works. And if the game you’re teaching is still in development, testing, and/or pitching, the rules are probably the only way your audience is kicking off their First Impression playthrough.

No pressure there.

Given the importance of writing a solid rules doc — and my compulsion towards procrastinating in the face of such a procedural and daunting task — I thought I’d share a few of the things I’ve learned over the years that can make the whole thing less arduous and more impactful. Contrary to my enthusiasm about actually doing today’s updates, here I’ll jump right in.

Write Your Rules In a Shareable Document

I currently use Google Docs, but I’ve worked for studios that require more secure systems (an internally secured Microsoft Teams network for example). Either way, the key is that whatever text document platform you choose to use, make sure it can easily be shared to other people when necessary. You’ll eventually want to send it out for rereads, audits, and edits by other designers and developers, and having it built to do that right from the start is just good standard operating procedure.

I’m partial to Google Docs because I can access and edit it from my phone, and it stores in my Google Drive, so I can cue up and ship a PDF of them whenever I need to, from wherever I am.

Be sure to date your file in the name and in the header/footer of the document, and be diligent in updating that date whenever you make major changes (I’m actually terrible at that last part, but I kick myself EVERY TIME I realize I’ve forgotten it). This is especially useful when you have printed copies that you need to put in order or match to the digital file. I like to use a six-digit format, visible in the image above; two digits for year, two for month, two for date. This keeps all your versioned documents in chronological order when sorted alphabetically, assuming the docs have the same name.

Google has a really useful “Versions” tool baked in that’ll let you roll back the clock to see things that you’ve left behind in the game’s evolution. If you’re working with a design partner on your game, it’s especially useful in that it tracks who made changes, and in what order those changes were made. If you’re at a mental recall moment where you can’t recall exactly when a change was made in the rules but you know which of you likely made it, you can shortcut by looking back just at the changes made by a specific person.

Having the tools to leave annotations on possible changes and reasons for updates in a sidebar to the document is critical. I guarantee there will be days where you can’t remember why you made a change, and the documentation of the corner-case discovered in playtesting will save you all kinds of distress. Having these notes available is even more critical when others start looking at the rules and asking what drove specific choices in how they’re written.

Start With a General Overview

Your first pass at a rules document should be very basic. There’s no sense in trying to get granular and specific in your rules when you’re first starting to put proverbial pen to paper. Just get the broad strokes in enough that you can refine things when the picture gets clearer. Focus on actually playing the game a few times to see which major structures work, and which need to be significantly reworked.

Your goal isn’t to be able to teach the game from this overview, it’s just to make sure you’ve organized your thoughts before you start describing what the game will be like to your audience. When someone asks “so what’s your new game like?”, you should be able to refer back to your overview to answer the most basic surface-level questions.

What goes in that initial overview? Oddly enough, I like to make sure I’ve got some of the most basic technical elements of the document itself framed in first, so that as I refine and change it, the “real” rules document just sort of emerges organically from the overview. Give it a working title. Put your name at the top of the page. Make sure your header/footer on the document has the date (see previous section). Make a brief section at the start that lists number of players, expected length of game, and target age range. These are the first questions anyone will ask about your game — there’s a reason they’re on the outside of every game box — and they’re critical to determining if the path your design takes is staying true to the target.

Next, frame in sections for general components, a short description of what playing the game is like, and the goal of the game. This isn’t the body of the overview; I’ll get to that in a minute.

- General components — You don’t need specific counts here, just an open-ended list of what players will probably see when they open the box. i.e., “property cards, player pieces, house and hotel tokens, a game board, money, dice, random effect cards”. We can figure out the exact number of those things and what their breakdowns are later.

- Description of the game — Tell us what the game is about and what the players will experience in a short paragraph. Is it cooperative or competitive? If there’s a strong theme, include that. Same goes for notable mechanical themes (“this is an economics game built on a roll-and-move structure, with auction and trading elements”).

- Goal of the game — What are players trying to do, and how will they know when they’ve won or lost? One sentence should be all you need here.

While you’ll adjust details here as the game takes shape over time and tests, most of these elements will keep their structure and intent right through the very last version of the rules.

The body of your overview begins with a section that explains how to set up the game. Again, you don’t need to get super-in-the-weeds here, but make sure that if your players need to know where the board/cards/pieces go before they actually begin playing, you’ve covered that. You’ll likely add diagrams here later, when the real rules writing kicks in.

After that, add a few paragraphs that explain how the game is played. Are there rounds or turns? Explain how turns are taken (assuming your game has turns), including a loose list of turn steps. Be sure to let the reader know when the game is over.

Get all of these worked out and written down, and you’re well on your way to going into some testing and rules refinement.

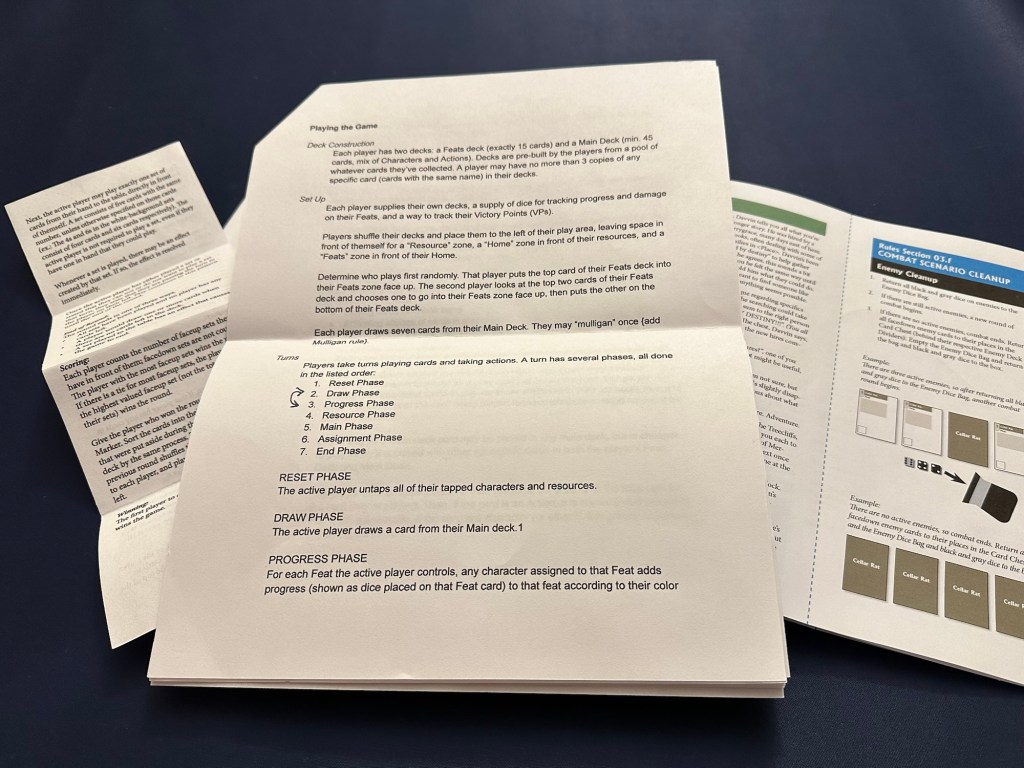

Print Out Your Document

It’s such an elementary step, but it has real value. For me, it’s sort of an emotional milestone in the process, even when it’s still just an overview; the game is just that much more “real” when I can look at everything out on a table.

Keep your printed copy with your prototype. As you play or make rules changes, make notes on it. Cross things out. Draw, edit, and annotate diagrams. Let your playtesters pick it up to refer back to and critique. They’ll probably eviscerate it, but that’s okay. You’ll make all kinds of revisions as you go, and tuning the rules is as much a part of game design and development as playtesting is.

Just be sure you’ve got that thing dated.

Make Diagrams

Diagrams are probably the most impactful thing you can add to a rules document. Most people are, at least in part, visual learners, and as the adage goes, “a picture is worth a thousand words”. Diagrams will help you show players how to set up and use the game components faster (and often better) than a wall of text.

Before I was a game designer, I was a graphic designer, so I’ve hard-wired myself over the years to organize things visually. Not everyone’s got the tools to make polished diagrams though, and if your game gets enough momentum to merit polished components and rules documentation, you’ll likely turn to an experienced graphic designer for an assist.

When you find the first point where a diagram will help explain your game (and it’ll happen very early, possibly even in the Overview stage), throw one together with whatever most basic tools you have available. Draw it with a pencil on notepaper and take a photo. If you have a physical prototype, set up the game on a table with decent light and take some pictures. If you use this last method, I suggest setting the game up indoors on a table you can easily reset things on days later; you’ll inevitably need to update your pics or add new ones to the document at some point, and general consistency helps the flow for readers.

Build and Iterate On Your Overview

I’m almost done with my procrastination and resigned to having to do the real work today, so I might as well tie it all together.

When your game is deep in conceptualization and has been played/tested a few times, writing a rules document from scratch SUCKS. It’s not exactly “too late” to start on a rules doc, but it’s not easy either, and the motivation to get it done is harder to pull together. Case in point, I’ve already got multiple versions of today’s documentation project done, and I still don’t want to have to grind through it again.

Once you’ve got the data and energy to take that leap into writing the rules, having the overview as a base is incredibly valuable. You’ll already have a lot of the game’s structure figured out and written down, so at this point it’ll be about adding the details and technical clarity that make the game teachable.

Your fist version of the rules will probably be awful. Unless you’ve been doing this for years, and sometimes even then, you’re likely going to have been too close to the project to be able to see the game through completely inexperienced eyes — and you need to explain the game for an audience with that inexperienced viewpoint. You’ll forget to add critical information because it’s so second-nature to you by this point. You’ll under- or over-explain things in ways that add confusion that you’ve been past for weeks. You’ll forget to update critical details in your last blitz rereading of them. Mistakes will be made.

I’ve talked a lot about playtesting in this blog. At some point, your game will reach a level of “completion” where you’ll need to include hands-off rules doc tests in the First Impressions sessions. You’ll give the game to your testers with a copy of the rules. Then you’ll sit back, listen, see what happens, take notes… and cringe. It’s not quite like learning to ride a bike; more like trying to teach someone else to ride a bike, and without the ability to show them how to adjust when they fail.

Frankly, maybe teaching bike riding isn’t the most apt comparison; when your student falls off their bike and faceplants on the pavement, they KNOW they’ve temporarily failed. There’s a really good chance that when your playtesters get something wrong with the written rules, they won’t know until ten minutes later, when they’ve moved past and forgotten the initial mistake. And it’s probably because your rules weren’t written clearly enough.

(There’s that impostor syndrome I mentioned up at the top.)

Regardless, the overview document you started with is the rock that all future rules clarifications and revisions are built on. To come full circle, go back to that sharable text document you started with and just keep adding to it and tuning the stuff that’s already there. Break things into clearly defined sections, and make important stuff easy to find. Print out a copy after every major revision and keep it with your prototype. Go all-in on your use of diagrams, and as your testers give notes, adjust them too; the printed copy will help a lot with that. Keep things as detailed as necessary, but as concise as possible (something I’m also often terrible at).

And the thing that’ll make organizing it clearest of all,

Don’t forget to update the dates.

PREVIOUS:

Preparing For the Playtesters’ Turns

Leave a comment