Playtesting your game sufficiently isn’t up for debate; it’s an absolute necessity. In my experience, that necessity is amplified when you’re working on a trading card game. The question in play is whether it’s better to test with physical prototypes or on digital platforms.

The two formats each have strengths and weaknesses, so for me, the simple answer is “why not both?”.

Apart from the “just cover all your bases” angle, there are some practical reasons for not making a committed choice to one or the other. You’ll learn different things faster by alternating your testing patterns. Both require quite a bit of prep work, but both are worth that time and energy spent — as long as you know what you’re looking to learn in that test.

Let’s look at the pros and cons of physical and digital playtesting. We’ll start old-school: classic shuffle-up-and-deal paper components.

Physical playtesting

Accessibility

When the average person hears “we’re going to playtest a tabletop game”, they’re immediately going to imagine a game on an actual table. This is a big piece of something called “accessibility”. Things that immediately conform to someone’s expectations don’t require a lot of explanation.

When I put a deck of cards in front of, say, my wife (very smart, very adaptable, maybe not so inclined towards digital tabletop gaming), she knows right away what to do with it, generally speaking. She can shuffle them, cut the deck, draw any number of cards specified, turn cards over in her hand and put them on the table in specific order and placement, and so on. It’s so easy that she doesn’t even think about how to do it, it just more or less happens as soon as she makes her decisions. We can jump directly into how to play the game, without losing time to how to play with the game. And when you’re playtesting, losing time to external factors is a big thing to avoid by any means necessary. Which brings me to…

Speed

Unless you’re testing a game with an elaborate set up process, odds are a physical, in-person playtest will have a a far more efficient run time than a digital one. It dovetails with the accessibility factor, though you’ll consistently see that even with playtest partners who are familiar with online boardgaming platforms, it’s still faster to just have pieces on a real table in front of you. Yes, there are many games where routines can be automated (shuffling and dealing cards, picking up a bunch of pieces from different parts of the game board, etcetera), but overall, you typically extend the length of a game by 20-30% by playing it digitally. And if part of what you’re testing for is how long a game takes — or how far you can push the envelope before players’ attention starts to drift — it’s best to get those measurements in a structure closest to the way the game will usually be played once its finished.

Building the prototype

This one’s complicated. There are certainly ways to streamline this process that happen in line with digital prototyping, and most of that is all front-loaded to start with. I used to do all my card layout in Adobe InDesign, then import that file into a separate layout formatted for my home printer. I then had an additional process for exporting all the cards into images I could upload to Tabletopia. So the first step of producing a physical prototype was effectively done at the same time as prepping the digital prototype, but overall the combined step was a little cumbersome.

Then I started using Component Studio (now in its 3rd version), and, as I wrote about a few weeks ago, it considerably changed my workflow, bringing the prep for outputting physical and digital prototype parts much more in line with each other. The initial build of a card template (currently) takes me a little longer than it used to in InDesign, but overall, edits and updates are much faster to handle now, cutting time off that part of production…

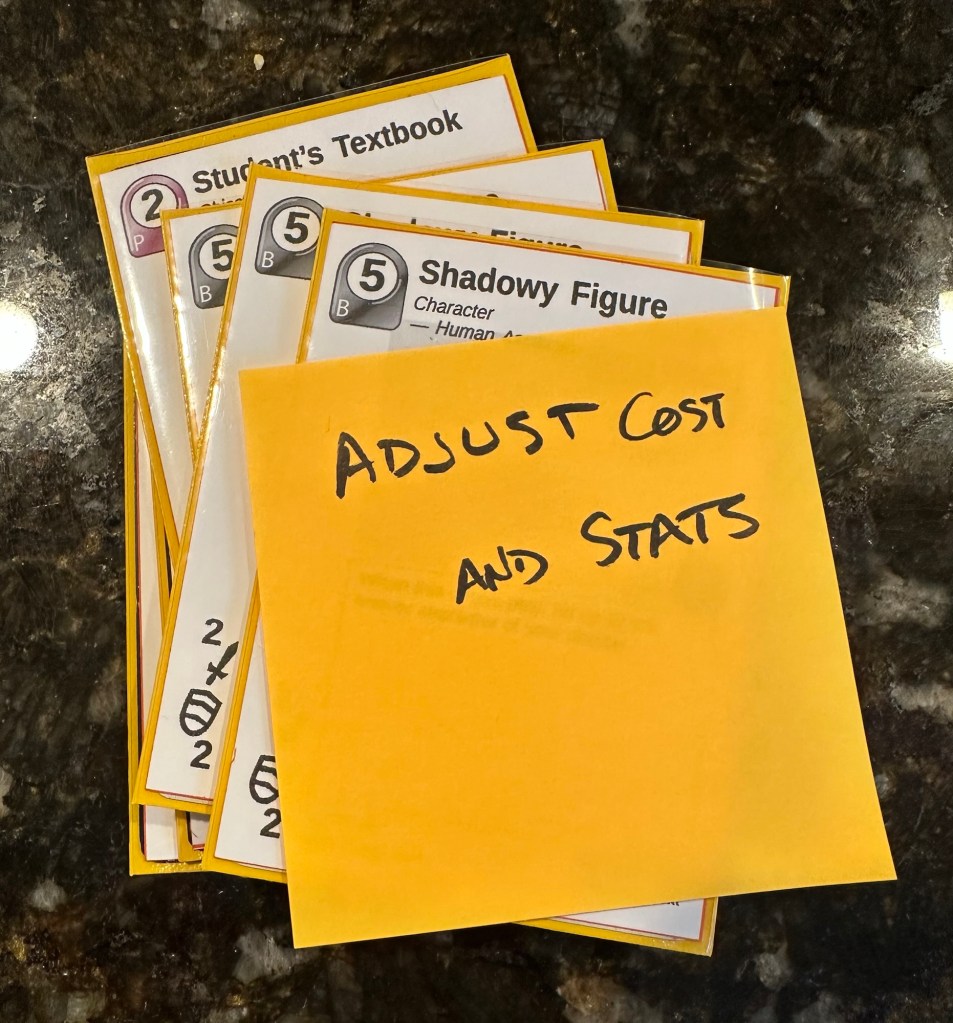

…But there’s still printing, cutting, sleeving, sorting, stickering, storing, buying supplies, and so on. As a result, I’d give the process of actually making (and updating) a physical prototype a big thumbs down, but a thumbs down you’ll probably have to learn to live with. This is the broccoli and lima beans of game making: you probably hate it, but will eventually learn you still hate it, even though it’s good for you. But you hate it.

“There’s got to be an upside though, right?”

There absolutely is. There is something big and valuable to be said for having a copy of the game you can just put out on your table at the drop of a hat. You don’t need to be logged into a computer, nor do your testing partners, so you can (usually) take it anywhere with you. It’s easy to make fast “Sharpie” edits directly on your prototype, or stick Post-It notes to things that you have ideas about in the moment. Having a physical object to interact with in a tactile fashion makes the whole thing feel more real, and as a result, the feedback is often more immediately actionable.

Exploring the game

This one could go in either jar, physical or digital, but for me, exploring the different angles of gameplay just feels better with actual game components in hand. This is especially true for me when the game is all about modular combinations of components, like in a trading card game.

When I want to play a TCG with a new deck of cards, fresh off the design line, I like having those cards there in a sortable box or spread out on the table. It helps me visualize the synergies and other possible play patterns in a format where I can quickly construct and deconstruct my deck and battle plan. I can do similar things digitally, but it’s generally slower and doesn’t have the frenetic soul that shuffling actual cards together does.

Unique components

The last major advantage I’m going to cover on this point is that sometimes you want your game to include a feature a component that just can’t easily be replicated in a digital prototype. Years ago, I designed a game that featured sand timers with one end concealed, so that when you refilled the timer you couldn’t see quite how much sand you were getting back. When Hurrican published it, they went all-out in making the sand timers look like these incredible post-apocalyptic action movie tanker trucks. In either form — blacked-out basic sand timers or awesome sculpted models — it would have required some serious custom coding to replicate the component for digital playtests. Plus, you’d lose the entire tactile interaction with a unique physical component that was so easy to achieve in a physical prototype.

Digital Playtesting

Range

By this, I’m referring to the sheer number of people you can reach with a digital prototype. When I spend the time and resources to make a physical prototype, I’m inherently limiting the number of playtests I can run concurrently to the number of copies I’ve built. I’m also capping my playtest partners pool at those within physical proximity of the prototype(s). A digital prototype has none of these issues.

As long as my testers have a computer with an internet connection and access to the platform I’ve built my game on, getting my game to in front of them is instant, no shipping required. It doesn’t matter where they are in the world. I can have thirty different players matching up two-at-a-time all at once and in 30 different states. Or countries. Or continents. (Quick, someone start building the extra 23 continents to get us to 30.)

I’ve even found that with a well-organized playtesting team, you can give them a community space like a Discord server and links to data recording tools (Google forms are easy to build and customize to what you’re trying to learn from your tests) so that you don’t even need to be “present” when the games are played. The sheer volume of data you can gather efficiently through digital playtesting is exponentially greater than the amount you’l get around a single table in one day; given the availability of the tool, it would be ridiculous to completely ignore digital playtesting.

That said, many gamers find that digital playtesting can lack a certain texture and soul (there’s that word again) that in-person gaming has. So once again, I’m back to recommending that your playtesting regimen include both digital and physical models.

Cost

I touched on this earlier, but when you’re building a physical prototype, there’s a lot of materials that get used, reused, recycled, and replaced. It can add up.

Not so much when you’re building digitally. Want to make an edit to your Tabletop Simulator build? No problem, you’ll never need to change an ink cartridge for that. Need to update your rules document in every copy of your prototype? Sure, there’s really only one copy, and it doesn’t cost you a single sheet of paper. Digital “cut and paste” requires exactly ZERO X-Acto blades and glue sticks.

If we want to break it all the way down to the initial overhead of buying a computer and paying for electricity and internet access, then sure, we can start evaluating the costs of a digital prototype compared to a physical one, but most of those costs apply to setting up your files for physical models too. So we’ll call that a wash and move on.

Editing and updating

Since we’re talking about the resources required to make your prototypes, we should also look at the resources needed to remake your prototype as you find things to edit, add, and update.

Once again, there’s a part of this that overlaps with physical prototyping in the setup of files. But once we move into producing the actual components for both models, digital prototyping can’t be beat for sheer speed and efficiency. When I’m playtesting digitally, I can get to the end of a game, see something that needs a wide-scale change, and knock out functional replacement parts in a few minutes. Change a spreadsheet, export a file, upload the fresh component into Tabletop Simulator, and voila, we’re ready to roll again. With a physical prototype, unless the edits are small enough that I can make the corrections with the aforementioned Sharpie, I’m probably looking at producing an entirely new set of cards/components, and all that that entails.

And that’s assuming there’s only one physical prototype to update.

Archiving and storage

As anyone who collects games will tell you, they begin to take up a lot of space quickly. Physical game prototypes are like that, but five-, ten-, or a hundred-fold. Ultimately, it’s usually just not efficient to keep a physical copy of anything but the most recent build. Files for making that physical model? Sure, keep all of those (and keep them well-organized); they don’t add any bulk in your workspace. But all those outdated, out-versioned paper copies? You’ve got to get rid of those, and that’s going to feel really wasteful. Because sometimes it is wasteful.

Digital prototypes will never clutter your desk or dining room table. You can save as many different setups and game states as your data-loving heart desires. If your notes and gathered testing results are kept online, you can have access to them anywhere, any time, and share them at will with anyone that needs them.

———

So there we go, lots to chew on there. Again, I recommend a healthy balance of both playtest article formats. It doesn’t quite double your workload (more like 1.6x), but it the benefits of each add up to WAY more than the sum of the parts.

And with that, I’m off to my latest favorite FLGS to do some in-person playtesting with actual paper cards.

Leave a comment