Time for another piece of the mystery to be revealed. In the last two weeks or so, I’ve shown some of the components I’ve kept hidden since this Disco Candybar project began, and I’ve pulled back the curtain on how the enemy “AI” system works. Today I want to share how the heroes’ part of the game engine works.

I’ll start this one at a point waaaay before Disco Candybar was even its own game concept. Years ago, I had an idea for a game that used a set of modular dice as the direct representation of a character and its abilities. I’d learned that vinyl cling material adhered really, really well to big, chunky, clear acrylic dice, while still being easily removed as needed. That discovery allowed me to change the faces of a standard die quickly on the fly — or slowly over time, as an associated story gave the player reasons to change or upgrade their skills and equipment. It was kind of like the customized dice element of Dice Forge, but on a much cheaper and more “manufacturing-friendly” scale.

Then, earlier this year, I had an opportunity to show a really rough game engine concept to a publisher that makes games with lots of dice. My goal was to show how we could innovate on some of their current game models by introducing a an element of “evolution over time” to one of their games. I mocked up a bunch of modular die faces on a material similar to the original prototype’s, stuck them to some dice that were almost the same as the originals, and threw them in a bag I could shake and pull a random array of customized dice from.

Unfortunately, the materials I had available weren’t quite as road-ready as the ones I’d had available eight-plus years ago, and while I could explain the concept clearly enough in the meeting, the prototype didn’t cooperate on camera. All in all, the demo fell pretty flat.

But sometimes the mild failure of what should have worked leads to a practical discovery of what could still work.

I’d pitched the enemy AI system that would go on to feature in Disco Candybar in that same call. Seeing as that part of the demo hadn’t crashed at all, I decided to consolidate the ideas into one. What if my customizable dice were just as simple as the enemy dice? I’d have to move the special modular effects off to something else, like a card, but those were still pretty easy to manufacture at a reasonable price (remember, this was all before tariffs). Plus, I could put clearer and more complete explanations of the functions on a card in a way that wouldn’t have been achievable on a tiny vinyl cling die face.

So I abandoned the modular cling-dice model entirely, and changed my hero build to a “totally normal dice with an array of cool interchangeable cards” structure. After all, if the enemies were using standard six-sided dice and cards with boxes to put them in, the same engine could potentially work for the heroes. I just needed to make sure that where the enemies worked without a need for conscious decision-making, the heroes’ version of that system gave the players some meaningful and interesting choices in each encounter.

Choice point 1:

The heroes get to select what character type they would be.

I hadn’t figured out how or when in the story of the game a player would acquire said equipment and ability cards, but a growing catalog of cards to pick from felt like a slam dunk way to show character growth over time. So I began with what I wanted the players to experience in any given encounter and left the “how did I get these?” for another day.

Having played a lot of adventure games in the last 40 years (geez, I’m old), I knew I wanted to let the players take on specific roles at the start of the story — a fighter, a magic user, a rogue/thief, a cleric, a hunter-type with a bow and arrow. All the trope-y hero character archetypes. I could make those characters feel different from each other through flavorful ability card designs. I could also structure those cards so that, at least in the beginning, a player could only optimize one specific character type at a time (I’ll expand on that idea in a little bit).

Choice point 2:

The heroes get to select what equipment and ability cards they get to bring into a battle.

For each of my five basic, starting character classes, I decided I would make three ability cards to show what sorts of things they could do. Everyone got one weapon card designed to fit the chosen character role, one skill card, and a third card that could be anything on-theme — a defensive element, an item, a second weapon, whatever made sense.

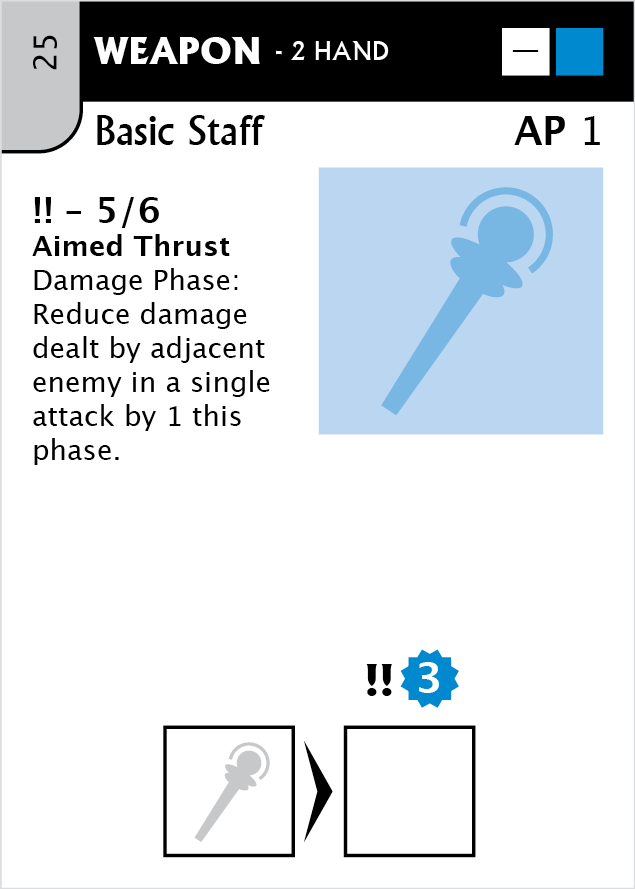

The Basic Staff deals 3 damage to the enemy this hero is facing as long as a blue die of any value is in the second slot. If the blue die in the second slot is a 5 or 6, it triggers the Armed Thrust special ability.

It takes four dice to get the full effect of Kinetic Wave. If the dice in slots three and four are blue, they’ll deal damage equal to the value shown on them to the adjacent enemy.

The Focus skill takes two dice to activate. As long as the second die is not white, the player can move either die to another card, allowing them to work around placement rules.

Choice point 3:

The heroes get to select what equipment and ability cards they get to bring into a battle.

Once the heroes got into the process of taking a turn within an encounter with enemies, the first choice at hand was “which two ability cards do I want to use this turn?”. I determined that while you could bring more two ability cards into an encounter (with some restrictions), the game was more fun when you had to decide what your best approach was from turn to turn. So I put a limit on how many ability cards you could activate at once. You could bring a menu of options to the fight, but you had to determine which two dishes — and ONLY two dishes — you were serving before you did anything else on your turn.

Choice point 2:

The heroes get to select who they face.

This is as basic as it sounds. If there are multiple enemies your party is facing off with, each player gets to choose which enemy their hero faces, and they put a marker in front of them. Still, it’s a meaningful choice.

Choice point 4:

The heroes get to select which ability cards they put their dice on.

Once you made that decision, the next phase of your turn worked a lot like the enemy AI: You pulled a set number of dice from your bag and rolled them, then you placed them on your selected ability cards in equal-or-descending order. There were some slight differences though.

Because you’d selected TWO cards to use for the turn, you now had the option of which of those cards would get dice this time around. You could put all your dice on one card, you could split them between the two, or, you could just ignore one or more dice that weren’t helpful back in your bag.

Now, for each hero, their dice bag started with six dice in it: two white dice, representing general effort towards whatever they’re doing, and four dice of a color specific to that character, representing their primary attribute that applies to their role. Red dice, for the fighter, represent strength. Blue dice represented the mage’s intelligence. Yellow was wisdom for the cleric, purple was cunning for the rogue, and green was dexterity for the ranger. These colors also corresponded to the ability cards I’d given each character for purposes of the eventual demo.

The rules for hero dice placement reflects the process for placing enemy dice. For whichever card you chose to put one or more dice on, the placed die had to be of equal or lesser value than the die that directly preceded it.

When you pulled the dice from your bag at the start of this step (three dice for the demo), you’d get some random grouping from your 2 white dice and 4 attribute/colored dice. But in addition to being able to choose which card(s) those pulled dice went on, you had an additional mini-decision the enemies didn’t have: if a colored die and a white die showed the same value after you rolled them, you could decide which order they were placed in. On an enemy roll, different dice of the same value were always placed black first, then gray. For the heroes though, they got to decide which die was better to place first.

So why might one die be better to place ahead of another die, and why would I choose to put each die on any particular card?

Because unlike the enemies, whose hit rate was determined just by whether their die was black or gray, hero cards had ways to hit on either your colored dice or your white dice (and sometimes both). If the little burst showed a damage number in a blue burst next to a die slot, then it would deal damage as long as a blue die (of ANY value) was in that slot. Likewise, if the damage number was in a white burst, it would hit as long as a white die was paired with it.

Your goal was to get sequences of dice of specific colors to line up with the damage symbols on the die slots, all while managing the “equal or descending” rule. Without the choices of which cards to activate and how to place dice of equal value, the players would just be mindlessly mimicking the enemy AI. With those choices, Disco Candybar had a compelling game engine.

There’s a lot more to the game than what I’ve described here, but this should give you some idea of the core process I was able to build around. I found ways to make certain die rolls trigger special abilities and effects on cards. I realized that players could ad new dice with different colors to their bags to give themselves access to a broader range of gear and skills. There’s a lot of character customization that can be done with this system, and it’s been fun (and educational) exploring all the ways a player’s dice and cards can illustrate growth and change.

I’ve shown you how the enemy AI system works. I’ve shown you the basic workings of the heroes’ system. Some time soon I’ll put it all together for you; maybe I’ll record a short demo video to show an actual fight between a fighter character and a wolf or something. We’ll see. In the meantime, here’s the scenario text and tear-out rules pages from the Lore Book that teaches players how to use their dice and cards for the first time. Enjoy!

PREVIOUS:

Goldbug Grows

Leave a comment